Study: Over Thirty Years of Farmland Investing Data Analyzed

Data analysis for this piece by Ashley McKillips.

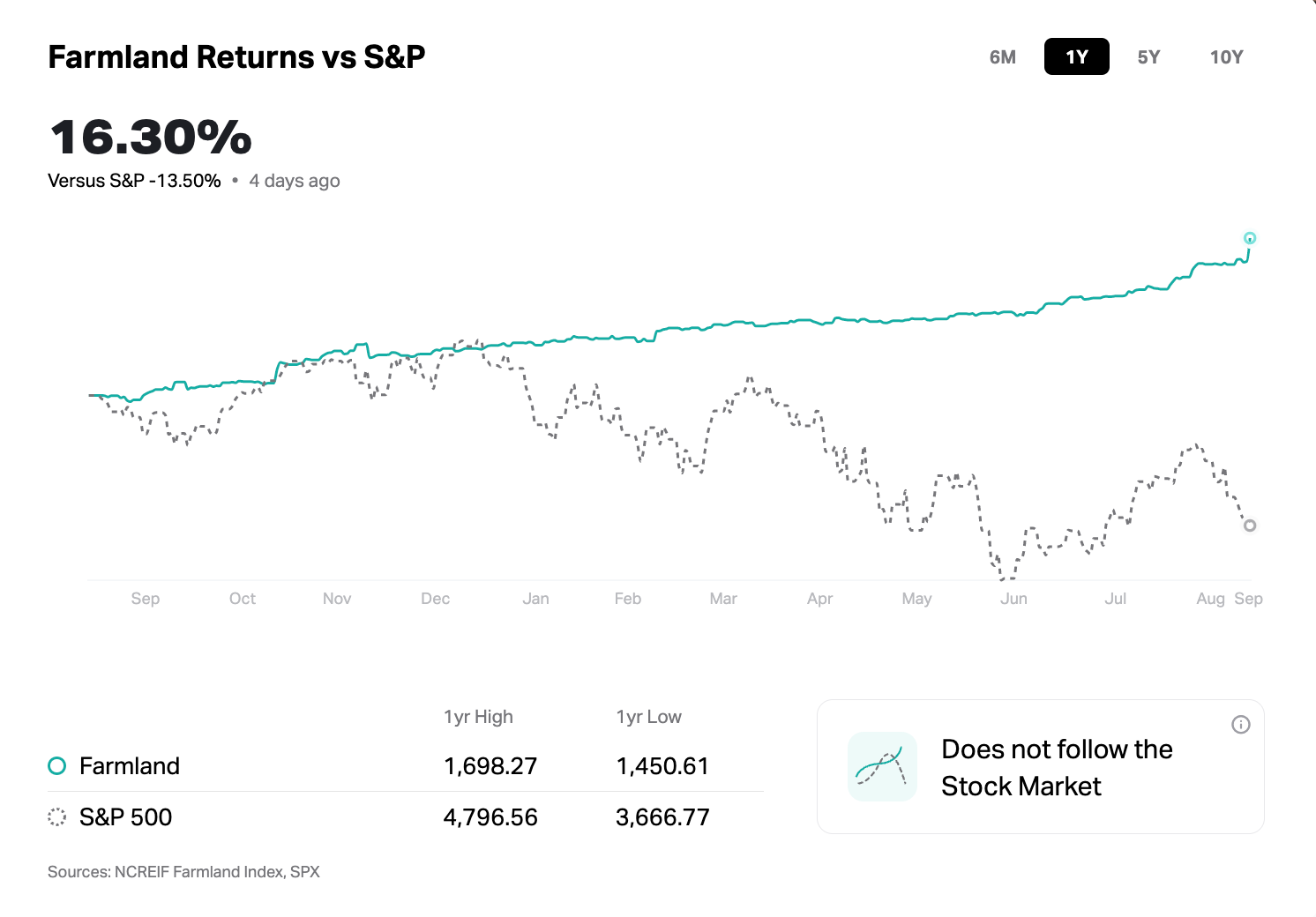

Economic fear and loathing may have peaked in the first half of 2022, but traditional assets like stocks and bonds are still at the mercy of weakening economic growth, surging inflation, and tightening monetary policy. Some experts say we’re already smack dab in the middle of a recession.

To weather this storm, savvy investors have turned to alternative assets with strong growth potential, stable cash flows, and low volatility. Farmland is an asset class that ticks all those boxes and even has a reputation as a recession hedge.

“Farmland has intrinsic value and shows consistent growth throughout stock market turmoil, making it an excellent hedge against recessions.”

Due to the limitless need for land coupled with its limited supply, farmland value typically appreciates over time. Next to that, farmland investments generate income through land rentals and revenue sharing from farming operations. Finally, since farmland can’t be traded at the click of a button, prices remain relatively stable compared to stocks and crypto.

So, how do you bring home the bacon with farmland investing? There are three main investment vehicles.

The first and obvious one is directly owning farmland and renting it out. But most investors don’t have this much cheese to spend—not to mention that they don’t want to become landlords. Option two is buying shares of farmland REITs (Real Estate Investment Trusts) or agriculture ETFs (Exchange Traded Funds). The problem is that most REIT and ETF share prices are about as stable as a chicken with its head cut off.

Your last bet is to invest in farmland through a crowdfunding platform like FarmTogether, which gives accredited and institutional investors access to vetted U.S. farmland.

And in case you’re thinking that the $15K minimum investment is a hard row to hoe, keep in mind that cropland costs $5,050 per acre on average in 2022. At an average farm size of 234 acres, you’d be looking at spending $1.17 million to own an agricultural property outright.

All of the sudden that minimum investment looks pretty affordable, am I right?

In this study, we’ll be using USDA data to analyze how farmland has performed as an investment asset over the past 3 decades, from January 1992 to January 2022. By the end, you’ll be able to decide whether farmland is an recession hedge worth adding to your portfolio.

Let’s rewind the clock and look at U.S. farmland’s performance through the years.

Farmland before the 90s:

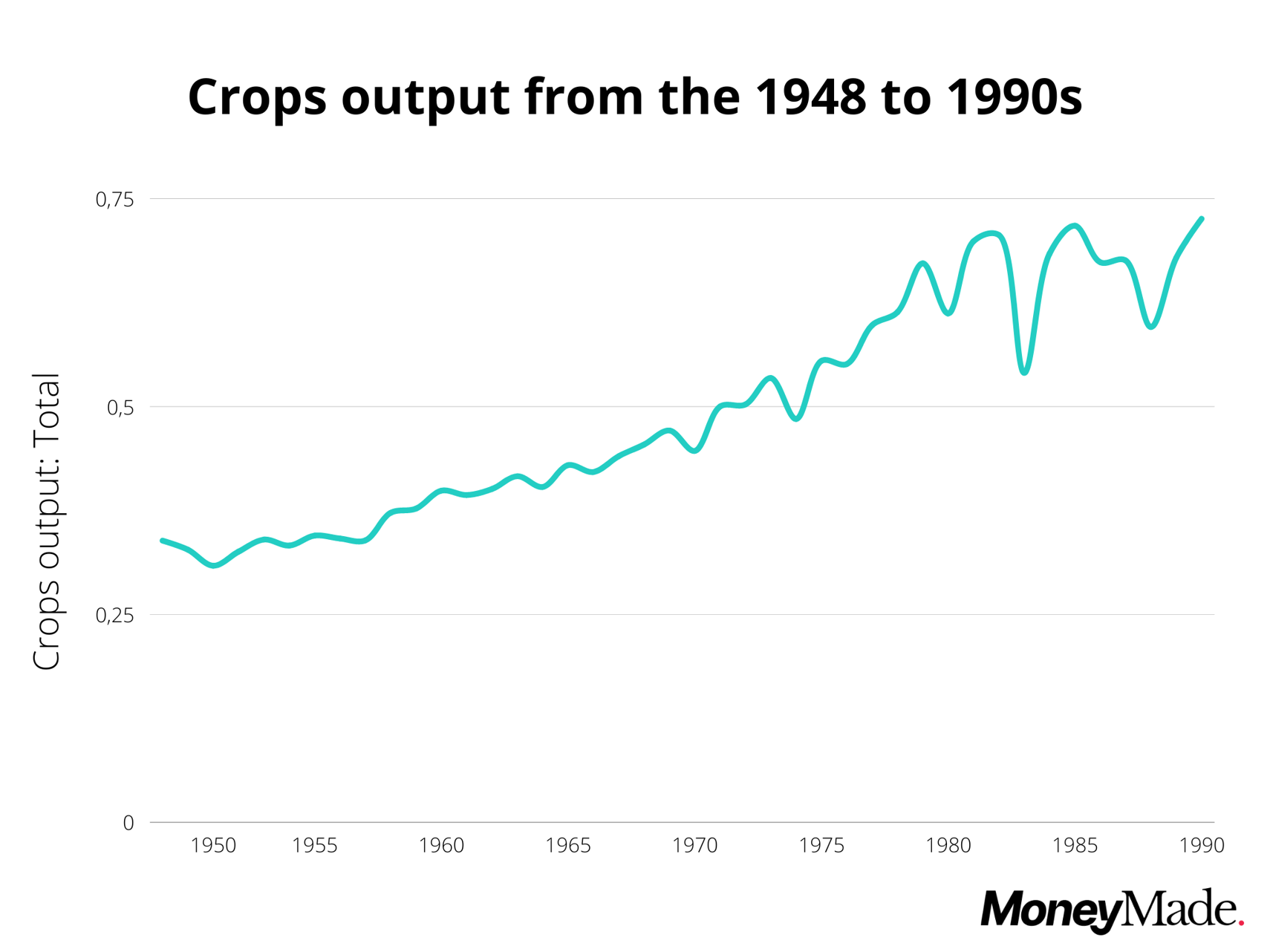

In the 1970s, the U.S. saw a major increase in the export of raw agricultural goods, and after a decade of growth, the industry began garnering investor interest. Greater institutional interest in farmland combined with stagnated economic growth in the 1980s led to greater government oversight and private resources for farmland investors.

The National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) stepped up its data collection, Agricultural Investment Associates, Inc (AIA) was formed, and the media turned its attention to farmland due to society’s growing concern for the enviroment in the 1980s.

During that 80s dip, crop output seesawed and the average value per acre of farmland shrank by about 7.5%. Nevertheless, these developments sowed the seeds of growth that farmland went on to experience in the 1990s.

Additional highlights of farmland before the 90s:

- Average inflation (1980-1989): 13.5%

- Availability: Percent of U.S. land for agriculture slowly begins to decline.

Farmland in the 90s

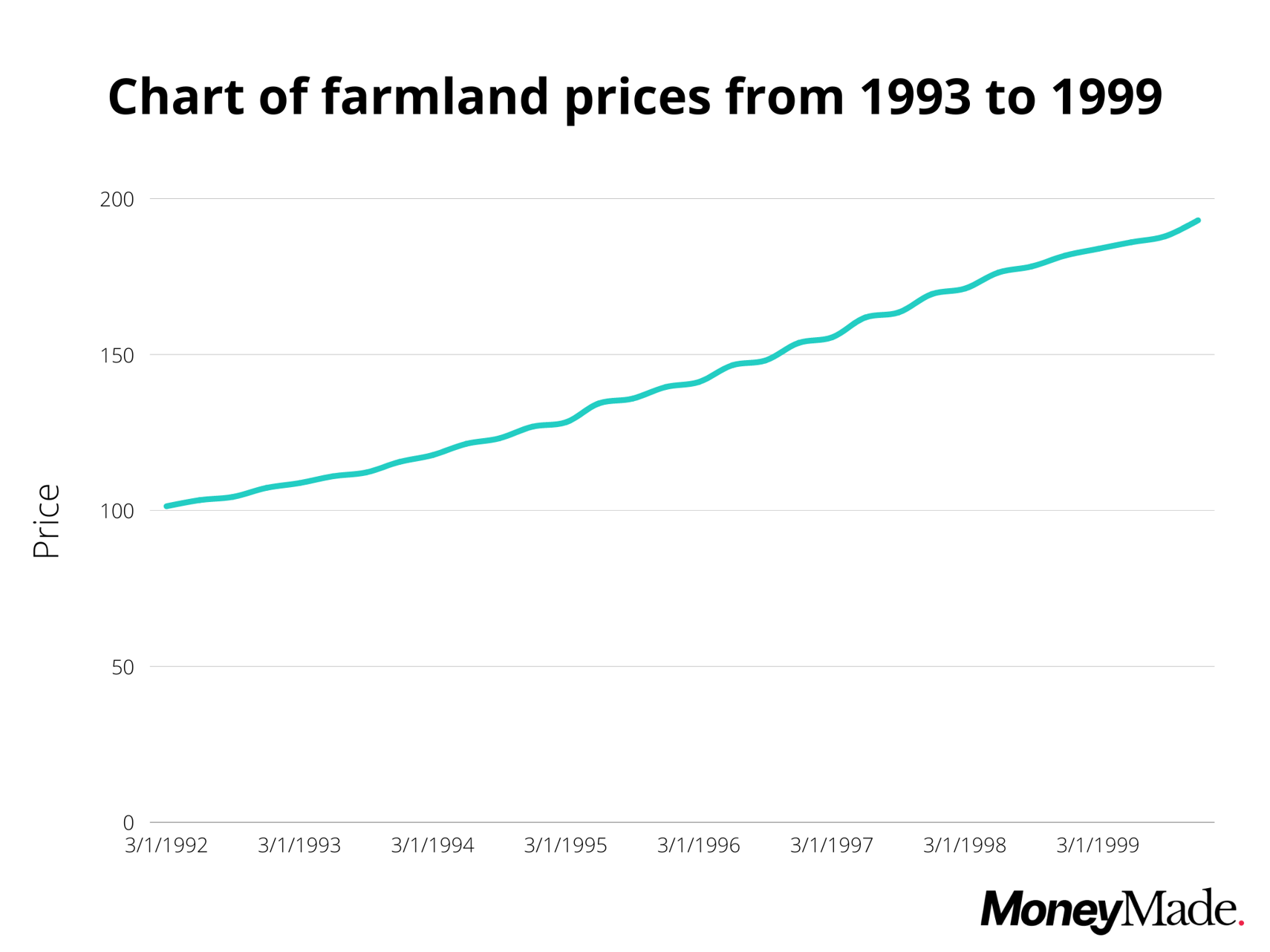

During the 90s, farmland prices switched trends from the 80s and returned 92%—a near 2x in value in 10 years. U.S. Farm real estate value per acre rose by 58%, with the biggest fortunes made in states like Michigan, Arizona, Utah, and Tennessee.

As a matter of fact, no state had a negative return for farmland values from 1990-2000. New Hampshire was the decade’s worst performer at 1.38%. So, back then, you could have essentially thrown darts at a map, bought up some farmland there, and made a nice return no matter what.

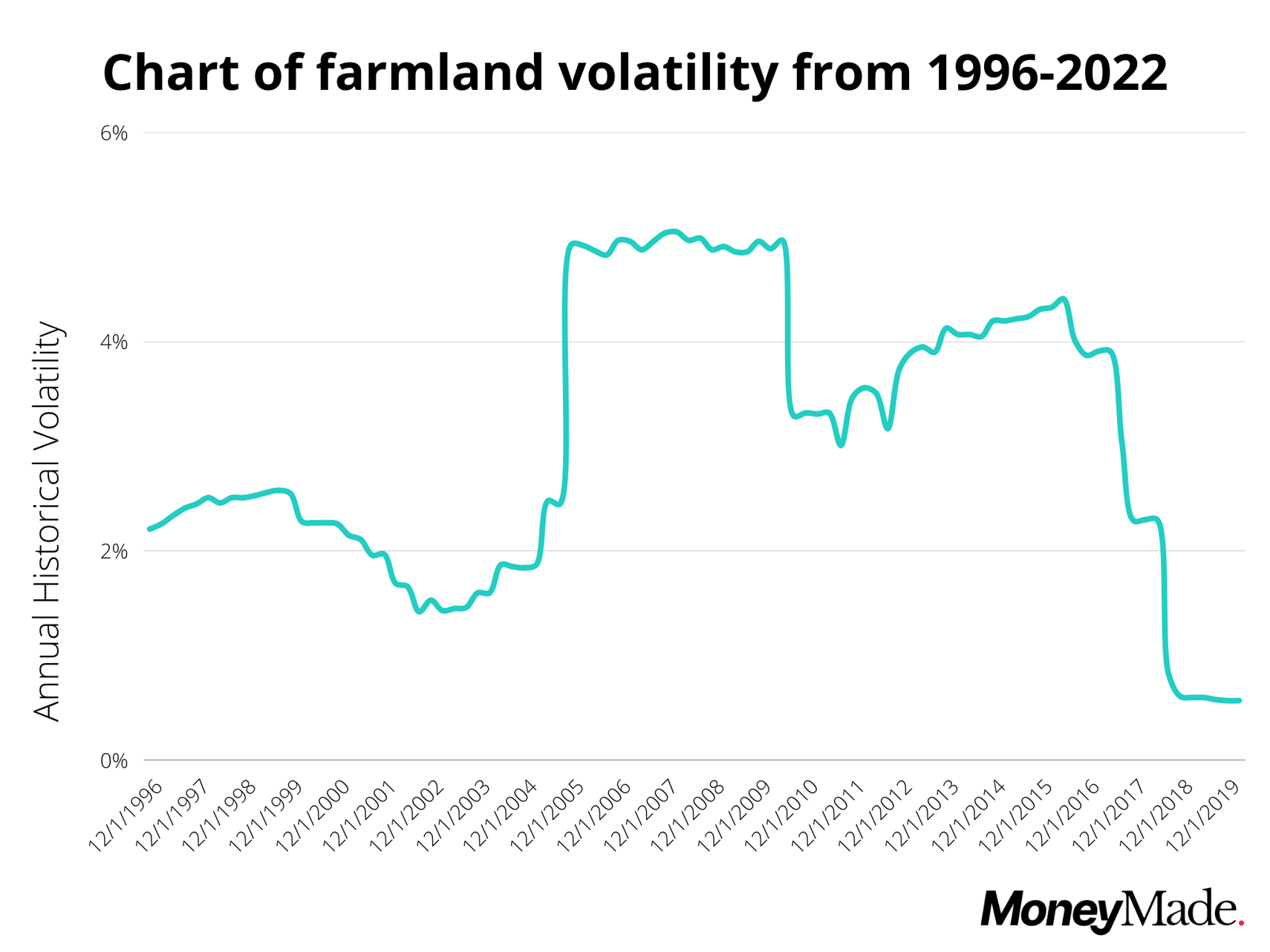

Farmland volatility in the 90s was as low as a horse’s hoof at 1.23%:

- Highest volatility per acre value: Southeast region

- Lowest volatility per acre value: Great Lakes

Additional highlights of the 1990s:

- Average inflation: 5.4%

- Correlation: Farmland was highly correlated (0.9616) with the S&P 500.

- Ownership: Data on foreign farmland investments wasn’t consistently collected.

- Productivity: Crop production grew by a hair.

Key takeaway: Farmland returned 92% and had an average volatility of 1.38%, while being highly correlated to the S&P 500.

Farmland in the 00s

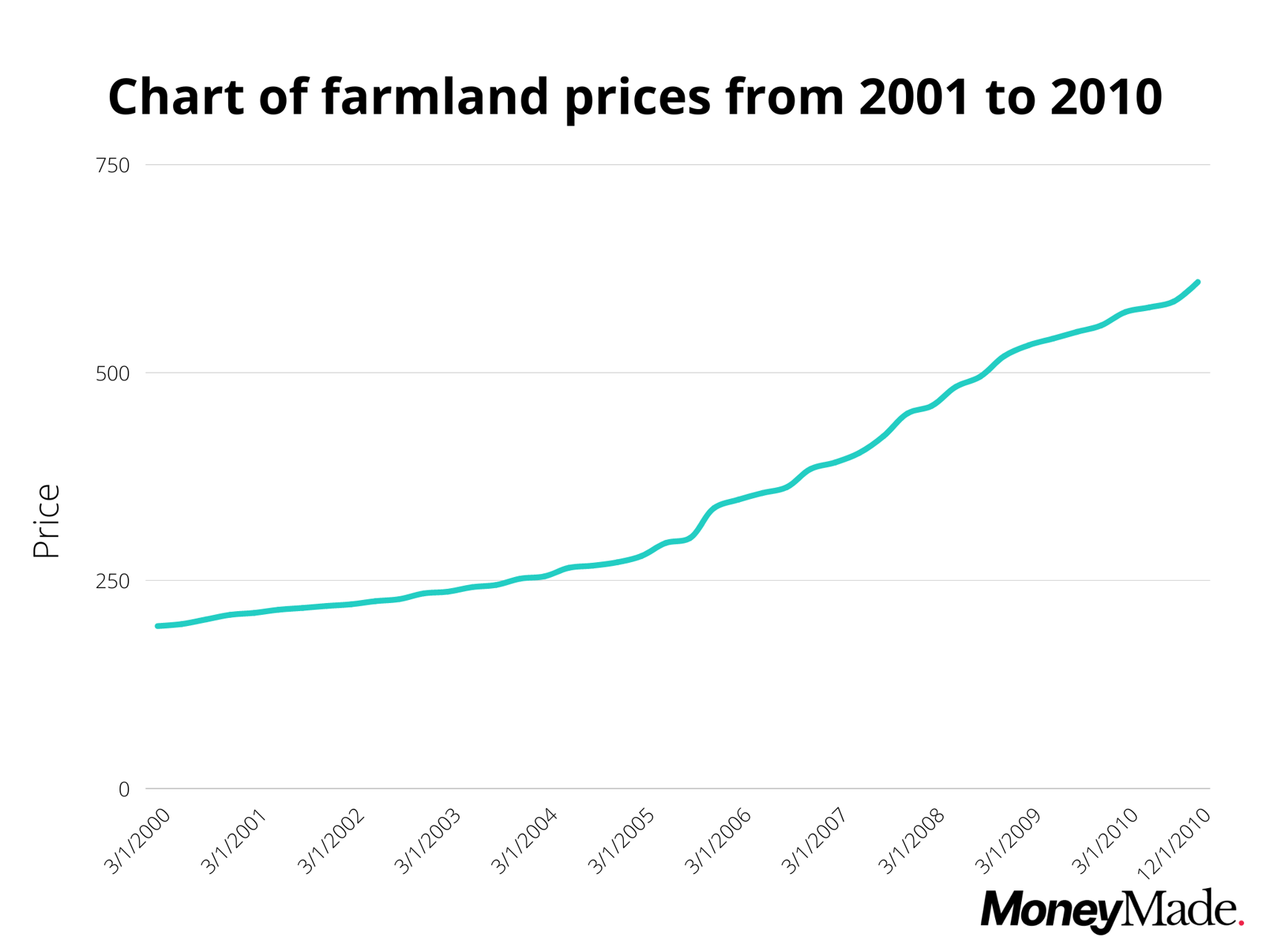

Farmers and investors alike were making racks on racks on racks during the 2000s, with farmland prices doubling for two decades straight. Farmland closed out 2010 with a 222.17% ROI, while U.S. per acre farmland value ballooned by 121%.

Arizona, Delaware, Iowa, South Dakota, and California all returned over 140% during this time period. By contrast, Alabama and Vermont made smaller (but still excellent) returns of 22% and 64%, respectively.

But that’s not all.

Lo and behold, the 2000s is the first time we saw farmland flex its recession hedging muscles by developing a -0.0355 correlation with the S&P 500. This was a complete 180-degree turn from the 0.9616 correlation we saw in the 90s. What catalyzed this inversion?

During the 2000s, farmland prices also took a defibrillator to the chest as the average historical volatility in U.S. farmland value per acre spiked to 4.33%. This spike happened right before the jenga tower of subprime mortgages came crashing down in 2007-08, with volatility remaining high throughout the housing crisis. Much of this volatility was concentrated in the Southeast and Mountain regions, while Lake and Delta states fared better.

Additional highlights of the 2000s:

- Average inflation: 3.8%

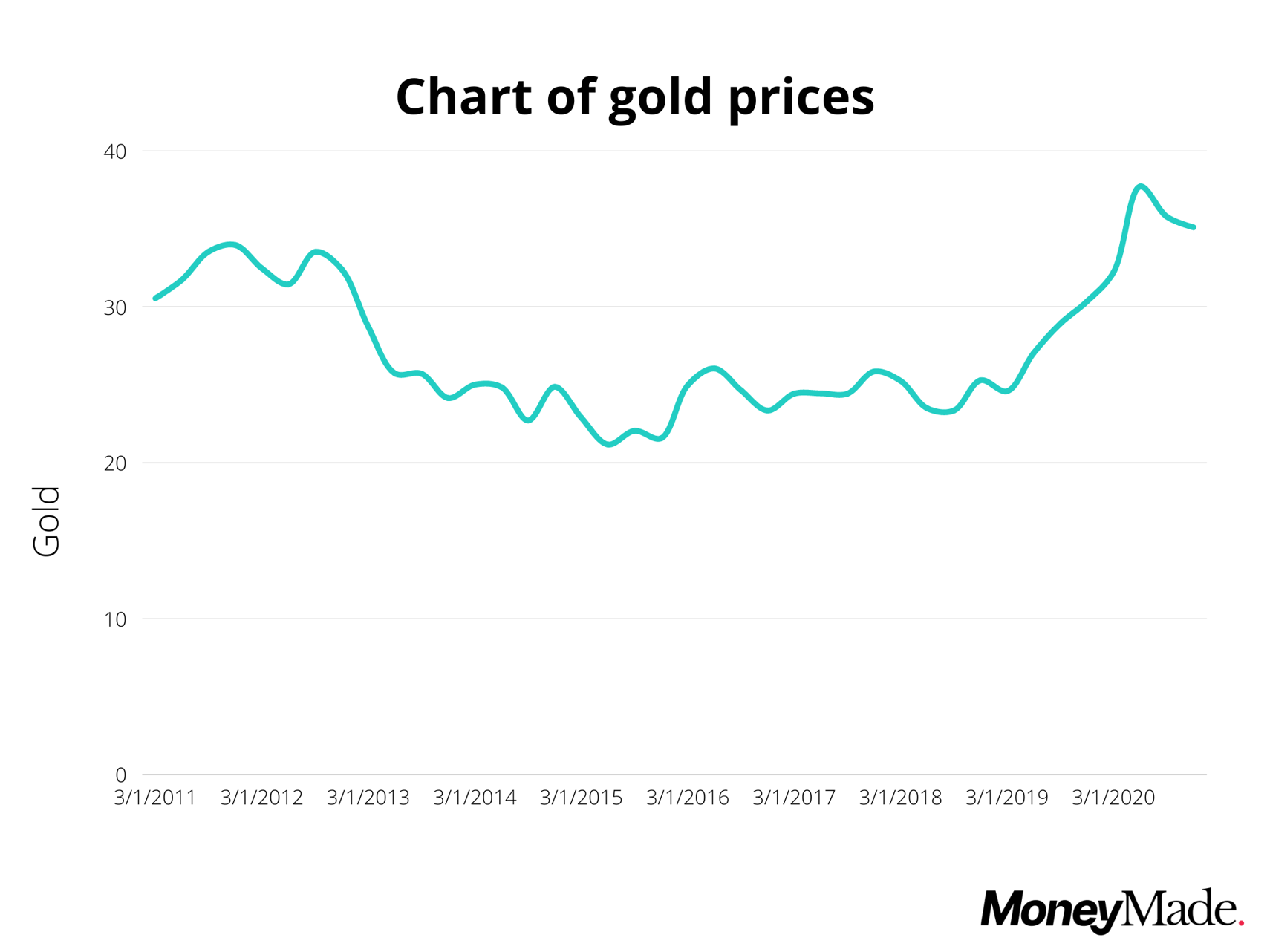

- Correlation: Farmland became highly correlated with gold (0.9614).

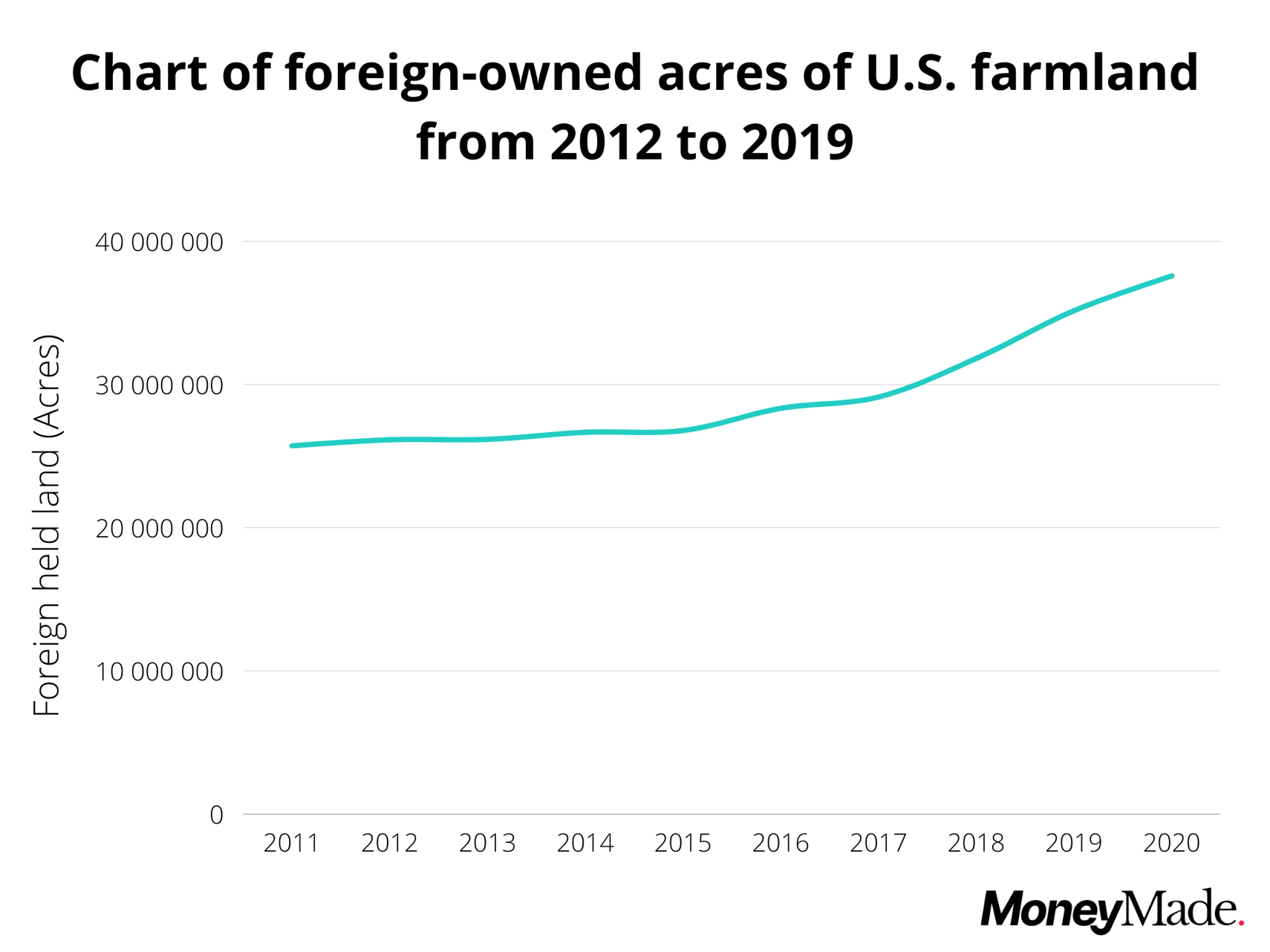

- Ownership: Around when the housing bubble burst, there’s a spike in foreign U.S. farmland ownership.

- Productivity: Crop output remains consistent throughout this period.

- Availability: Percent of U.S. land for agriculture continues to decline.

Key takeaway: Farmland decoupled from the S&P 500 and returned 222.17% with an average volatility of 4.33%—all the while foreign investors continued to buy U.S. farmland.

Farmland in the 10s

After seeing prices double for two decades straight, some of you might be disappointed to see that farmland merely returned 112% from 2010 to 2020. And while the average price per acre of farmland across the U.S. increased by 41.42%, but growth was down compared to the previous decade.

The top performing states in the 2010s were South Dakota, North Dakota, Idaho, Nebraska, and California with farmland returns exceeding 57%. Georgia was the first negative performer found in this study at around -3% farmland returns.

During this time, Farmland sprang back into high positive correlation with stocks and gold:

- S&P 500: 0.9270

- Gold: 0.0653

In contrast to farmland, the S&P 500 returned 255.2% during the 2010s. But, the context matters here. During the 2010s, stocks were riding high off the longest bull market in history—complete with low interest rates and trillions of dollars of liquidity pumped into the markets.

But with rates rising and liquidity drying up like the Sonoran Desert, farmland’s consistent growth—year in and year out—made it a welcome addition to a diversified portfolio.

Farmland volatility swung a bit after the 2008 recession, but firmly entered a downtrend in 2016 until it reached near zero volatility after 2018. The highest volatility regions were the Northern Plains, Corn Belt (American Midwest), Lake and Southern Plains. However, the Appalachian, Delta, and Mountain regions had lower volatility.

Additional highlights:

- Average inflation: 3.2%

- Productivity: Crop output is mostly consistent.

- Ownership: International holdings are reported to represent 1.66% of farmland ownership in 2020.

- Availability: Percent of U.S. land for agriculture continues to decline.

Key takeaway: Farmland returned 112% at an average volatility of 1.36%. But farmland once again became positively correlated with the S&P 500.

Is Farmland a good investment?

To fully answer this question, we need to consider three key farmland variables: historical returns, volatility, and price correlation.

Farmland’s growth potential

Key details:

- Best performing regions: Northern Great Plains and Great Lakes

- Worst performing region: Southeast region

- Moderate performing regions: Pacific Coast, Corn Belt (American Midwest), and Southern Plains

The USDA’s latest tally also shows that both cropland and pastureland value has increased by 14.3% and 11.5%, respectively, from 2021.

And if you think that’s something, hold onto your straw hats because the long-term gains are even juicier. According to our data, if you had held Farmland from 1992 to today you would have made a 1,436% return on investment. Mind you, this level of growth does require a long-term time horizon and land returns vary by state.

Key drivers behind farmland’s dizzying returns include:

- Availability: Farmland prices increase as farmland availability decreases (-0.8179 correlation).

- Foreign investment: Farmland prices tend to increase with international investment in U.S. farmland (0.1931 correlation).

Farmland’s low volatility

Key details:

- Lowest volatility regions: Great Lake states

- Highest volatility regions: Southeast

Farmland has also been a stable asset to hold during market downturns, with an average annual historical volatility (HV) of 2.91%. For context, the S&P 500’s average annual HV is 15.42%. The Mississippi Delta, Great Lakes, and the Appalachian regions all provide fertile (and low HV) ground for your farmland empire.

Farmland’s correlation to other asset classes

Farmland and the stock market: are they like two peas in a pod as far as price movement goes? It all depends on the time frame.

Here’s how farmland correlates to stocks and gold:

- S&P 500: 0.8993 (30-year period)

- Gold: 0.7328 (~18-year period)

Like Shakira’s hips, the numbers don’t lie. Over the long-term time horizon, farmland moves closely with traditional asset classes and alternatives—mostly with stocks and the least with an asset like gold.

Hold on. Did we just nuff out farmland’s value as a recession hedge? Not quite. In smaller time frames (particuarly during recessions), like the early 2000s housing crisis, farmland has a negative correlation to other asset classes.

Bottom line: Is farmland a good investment?

Well, for one, farmland is intrinsically valuable thanks to its crucial role in the production of agricultural commodities. Besides this, the farmland asset class shows consistent growth throughout periods of stock market turmoil, making it an excellent hedge against recessions.

So if you’re a long-term (10+ years) investor looking to diversify your portfolio with minimum added volatility, then the answer is a resounding yes.

Sources

- Agricultural Land Values. Retrieved 8/31/2022 from United States Department of Agriculture.